Fever in the Returned Paediatric Traveller, Part 2

Syndromic Thinking, Smarter Tests, Infection Control Ceasures and Public Health Triggers

Welcome back!

In Part 1, we focused on the power of a GREAT travel history—covering

Geography/ Timing

Risk behaviours and exposures

Eating/ Drinking, Extra precautions

Activities, Accomodation, Age-specific behaviours

Traveller type (VFR, tourism etc) and host factors.

A detailed history, when paired with a careful examination, gives us something invaluable: a clinical syndrome.

Now, in Part 2, we use that clinical syndrome as a springboard into diagnosis, testing, infection control, and public health action.

From Syndrome to Specifics

Clinical syndromes allow us to follow a deliberate and systematic diagnostic approach to identify a specific infectious agent, leading to a more focused evaluation while keeping the differentials open for consideration.

A syndromic approach allows for structured reasoning—narrowing likely pathogens based on:

Incubation periods

Geography

Exposure risks

For example, a fever occurring 2 weeks after returning from travel to India is less likely to be dengue (typical incubation period 4-7 days) and more likely to be malaria, for instance. It is challenging, and perhaps not entirely useful, to provide a comprehensive summary of all infections and their incubation periods; however, knowing the most common infections by region helps keep our focus sharp.

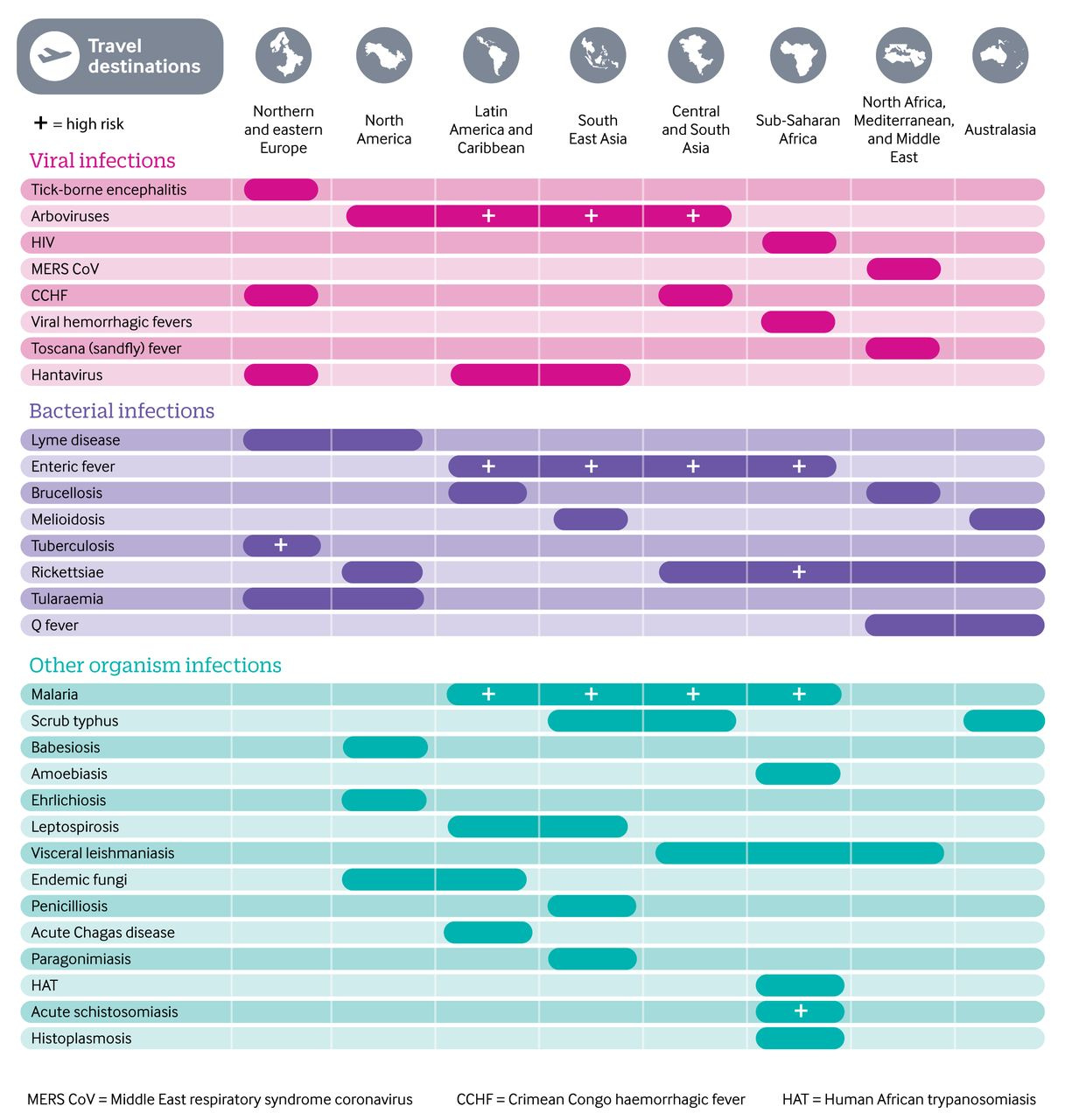

Common Infections by Geographic Region

Adapted from the CDC’s Yellow Book:

Want a visual? Check out the infographic from BMJ: Fink D et al. Fever in the returning traveller. BMJ 2018.

Testing: Start Smart, Then Sharpen Your Focus

Start with first-line investigations applicable to nearly all febrile travellers. These are usually included in most Emergency Department guidelines.

Full Blood Count

Urea, Electrolytes, Creatinine

Liver Function Tests

C-reactive Protein

Blood Cultures

Urine Culture

These help assess severity and hint at certain patterns, though they may be normal in the early phase of illness:

Eosinophilia? Think parasites.

Thrombocytopenia + leukopenia? Think dengue.

Anaemia + high CRP? Think malaria or typhoid.

Next step: Tailor further tests based on syndrome, incubation period and geography. For example:

Fever + CNS symptoms + Respiratory symptoms; 3 days post-return from India. Your options, for example, may include:

Blood

Microscopy- Malaria thin and thick films

Culture- Blood culture

Serology- Dengue serology, Japanese encephalitis virus serology

Molecular- N. meningitidis, S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae

CSF-

Microscopy- Gram stain, India ink

Culture- CSF culture

Serology- Dengue/ Japanese encephalitis virus serology, etc

Molecular- N. meningitidis, S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, HSV; or other multiplex PCR panels e.g. BioFire Meningoencephalitis panel etc.

Respiratory

Microscopy- Induced sputum for acid-fast bacilli (if suspecting TB)

Culture- Sputum culture

Serology- Not useful

Molecular- Respiratory viral PCR

May consider other immunological tests- Tuberculin skin testing or IGRA for TB.

Refer to the Ultimate Guide to Microbiology Test Requests to learn more about selecting the best specimens and test types.

Check out the table for download at the top of the page for common causes of fever in the returned traveller based on clinical syndromes, and the suggested microbiological testing.

Infection Control: Identify and Isolate

The travel history can reveal some clue on risks to the healthcare system, especially if the child has ticked the following checkboxes:

Was hospitalised overseas

Is unvaccinated- think measles!

Was exposed to high-risk settings (farms, refugee camps, sick contacts)

Contact with multi-resistant organisms (MRO)

Recent antimicrobial use

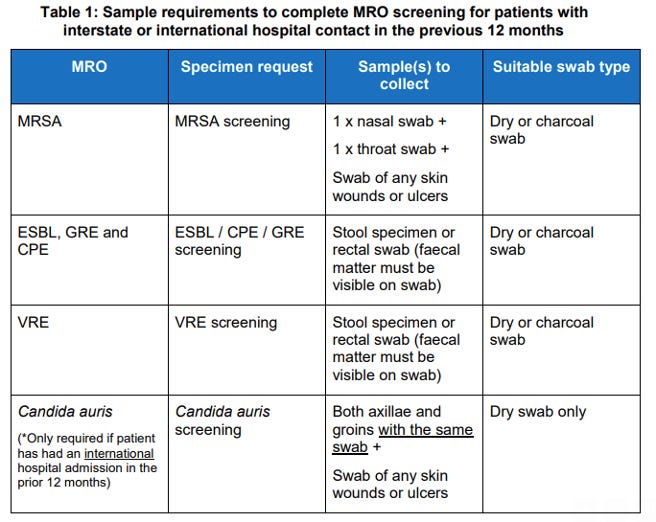

Screening swabs may be indicated in addition to diagnostic tests—check your hospital’s infection control protocol. An example from a hospital where I work:

Public Health: When to Notify

All jurisdictions maintain a list of notifiable conditions:

Urgent notification (e.g. meningococcal disease, measles) → due to high transmissibility and outbreak potential.

Routine surveillance (e.g. pertussis, rotavirus) → notify within 72 hours.

High-consequence threats (e.g. viral haemorrhagic fever) → notify public health and senior leadership immediately upon suspicion.

Be familiar with your local notification form (see example) and reporting timelines.

In the Next Post...

We’ll take a deep dive into travel to Bali, a top destination for WA families. Using the GREAT history, we’ll highlight common infections and high-yield questions to ask.

References:

Fink D, Wani RS, Johnston V. Fever in the returning traveller. BMJ. 2018 Jan 25;360:j5773. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5773. PMID: 29371218.

Flores MS, Hickey PW, Fields JH, Ottolini MG. A "Syndromic" Approach for Diagnosing and Managing Travel-Related Infectious Diseases in Children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2015 Aug;45(8):231-43. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2015.06.005. Epub 2015 Aug 5. PMID: 26253891; PMCID: PMC7106018.

Ralph Huits, Davidson H. Hamer, and Michael Libman. Post-Travel Evaluation of the Ill Traveller. CDC Yellow Book: Health Information fro International Travel. Accessed 22nd May 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/yellow-book/hcp/post-travel-evaluation/post-travel-evaluation-of-the-ill-traveler.html