Guarding Little Hearts: Tackling Infective Endocarditis in Children

From subtle clues to critical calls. Key insights, diagnostic pearls, and treatment frameworks for infective endocarditis in children

Last week, I encountered a surprising twist that reminded me how important it is to keep a broad differential—especially when fever persists in complex kids.

A young child with congenital heart disease and immunodeficiency presented with six weeks of on-and-off fevers after returning from overseas. Fever in the returned traveller? Didn’t quite fit… the long list of differentials loomed large—bacterial, viral, fungal, TB, and everything in between. But what stunned me was the final diagnosis: Infective Endocarditis!

A week later, the ID team were consulted on two other cases of infective endocarditis. Good things happen in threes! All were culture negative.

It’s a uncommon diagnosis in children, but one we absolutely cannot afford to miss. With an incidence of only 0.43–0.69 cases per 100,000 children–year; it’s uncommon—but increasingly relevant due to more medically complex pediatric patients.

This is quite a lengthy post for a diagnosis we seldom see. For a straight-to-the-point summary to review the key points, download it here.

Who’s at Risk?

In kids, IE has different risk factors than in adults:

Congenital Heart Disease (CHD): ~50–70% of pediatric cases. Turbulent flow → endothelial injury → bacterial seeding.

Cardiac Surgery & Prosthetic Material: Valves, conduits, patches = potential infection sites.

Central Venous Catheters (CVCs): ICU kids are high-risk.

Immunodeficiency: Congenital (e.g., agammaglobulinemia) or acquired → broader pathogen spectrum.

Previous IE: Lightning can strike twice.

IV Drug Use: More relevant in teens.

Healthcare Exposure: Especially with MDRO colonization.

The Microbial Lineup

The causative pathogens vary with age, setting, and host factors.

Staph aureus (MSSA/MRSA)- Acute, destructive IE. MRSA in healthcare settings.

Viridans Strep (VGS)- Subacute. Think dental hygiene/procedures.

Enterococci- Intrinsically resistant. GU tract or healthcare-associated.

Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci (CoNS)- Prosthetic valves, CVCs.

GNB (E. coli, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella spp)- Increasingly seen, especially with healthcare contact, CVCs, or immunosuppression. ESBL-producers are a growing threat.

Fungal pathogens (Candida spp. > Aspergillus spp)- High mortality. ICU, prematurity, immunocompromised, or after prolonged broad spectrum antibiotics.

HACEK (Haemophilus spp., Aggregatibacter spp., Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella kingae) – classic but less common causes, often described as fastidious.

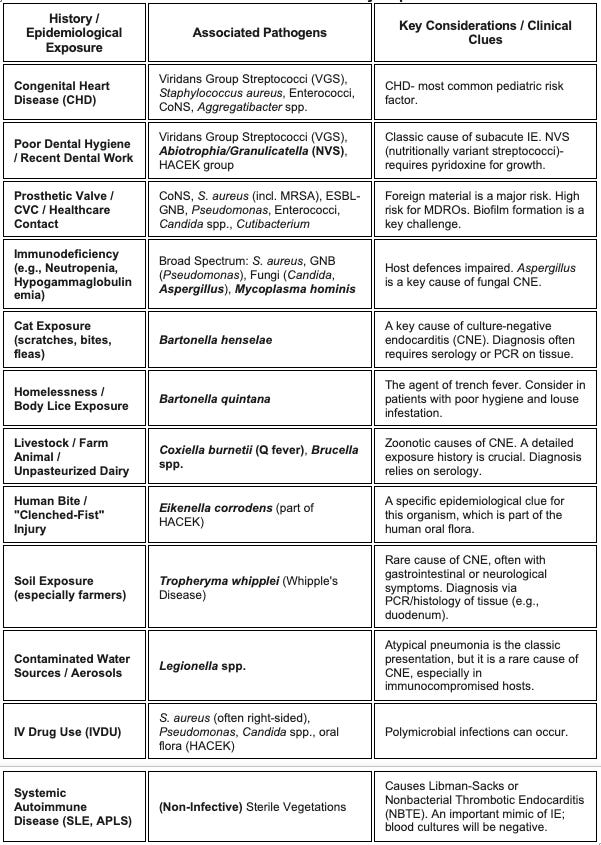

Clues from History and Epidemiological Exposure

Spotting the Signs: The Clinical Picture

Pediatric IE can be sneaky. Symptoms are often nonspecific, especially in infants:

Fever: Most common symptom, often prolonged or "grumbling".

Malaise, fatigue, poor feeding, weight loss.

New or changing heart murmur: A critical sign!

Splenomegaly.

Peripheral Manifestations: Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, Roth spots, splinter hemorrhages – classic but less common in children than adults.

Embolic Phenomena: Can lead to stroke, kidney infarcts, and splenic abscesses.

Heart Failure: A severe complication, often due to valvular destruction.

Immunocompromised children may have a blunted inflammatory response, with fever being the main or only sign.

Updated 2023 Duke-ISCVID Criteria: Summary Table

Definite Infective Endocarditis (IE):

2 Major Criteria

1 Major + 3 Minor Criteria

5 Minor Criteria

Possible IE:

1 Major + 1 Minor

3 Minor Criteria

Here’s my attempt at summarising the updated 2023 Duke-ISCVID criteria in a table:

Major Criteria:

Minor Criteria:

Rules on Blood cultures:

≥2 (ideally 3) sets before antibiotics

Aerobic & anaerobic bottles are ideal. The routine paediatric bottles are enriched, but risk losing your anaerobes.

Age-appropriate volume: volume = sensitivity (e.g., 1-3 mL per bottle for an infant, up to 5-10 mL for older children).

Tissue specimens= priceless

If the patient undergoes surgery, send the excised vegetation or valve tissue for:

Gram & fungal stains

Histopathology

Bacterial/fungal culture/(Mycobacterial culture)

Molecular diagnostics (16S/ITS or pathogen-specific PCR)

When to Refer for Surgery

Severe valvular dysfunction/heart failure

Persistent bacteremia >7–10 days

Large vegetations (>10 mm) + embolic events

Fungal IE (especially Aspergillus spp)

Abscess, fistula, prosthetic valve dehiscence

Laboratory Identification Methods

We’re back to the same framework- Microscopy, Culture, Serology, Molecular.

Plasma Microbial Cell-Free DNA (mcfDNA) Sequencing: I will just mention this “Karius test”, which is essentially a blood test that uses metagenomic sequencing to detect and identify microbial DNA circulating in the blood. Think of it as a "liquid biopsy" that can identify over 1,500 different pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, from a single blood sample.

When Cultures Are Quiet: Navigating Culture-Negative

What happens when you have a high suspicion for IE but the blood cultures are negative? This is the challenge of Culture-Negative Endocarditis (CNE), which can account for up to 20-25% of cases. It's also vital to remember that not all vegetations are infectious.

Clearly, when culture fails, utilise other methods of detection such as serology and molecular methods!

Causes of “Culture-Negative” Infective Endocarditis (CNIE)

Prior Antibiotics. This is the most common reason.

The "Hard-to-Grow" Crew (Fastidious & Atypical Pathogens):

HACEK Group: Modern culture systems have improved their detection, but prior antibiotic use can still lead to negative cultures. Kingella kingae is particularly relevant in young children.

Nutritionally variant Streptococci such as Abiotrophia/Granulicatella

Fungi (especially Aspergillus spp.): A huge concern in immunocompromised patients or those with CVCs. Blood cultures for Aspergillus are notoriously negative

Other: Cutibacterium, Brucella spp., and Mycoplasma spp.

Unculturable with current techniques-

Bartonella spp.: A major cause of CNE in children, often linked to cat scratches. It can present subacutely with large, friable vegetations. Diagnosis often requires high suspicion, serology, and/or tissue PCR.

Coxiella burnetii (Q Fever): A rare zoonotic cause in children, associated with exposure to livestock. Serology is key.

Tropheryma whipplei (Whipples)- Rare. Often linked to soil exposure (e.g., in farmers) and typically presenting with GI or neurological symptoms. Diagnosis is by PCR/histology of tissue.

Non-Infective Mimics of Endocarditis

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Linked to autoimmune disorders, particularly SLE, and malignancies

Sterile valvular vegetations form and embolise, clinically mimicking in many respects culture-negative IE. Usually affects mitral valve

Neoplasia associated

Atrial myxoma, marantic endocarditis, neoplastic disease, and carcinoid

Autoimmune associated

Rheumatic carditis, SLE, polyarteritis nodosa, and Behçet disease

Postvalvular surgery

Thrombus, stitch, or other post-surgery changes

Miscellaneous

Eosinophilic heart disease, ruptured mitral chordae, and myxomatous degeneration

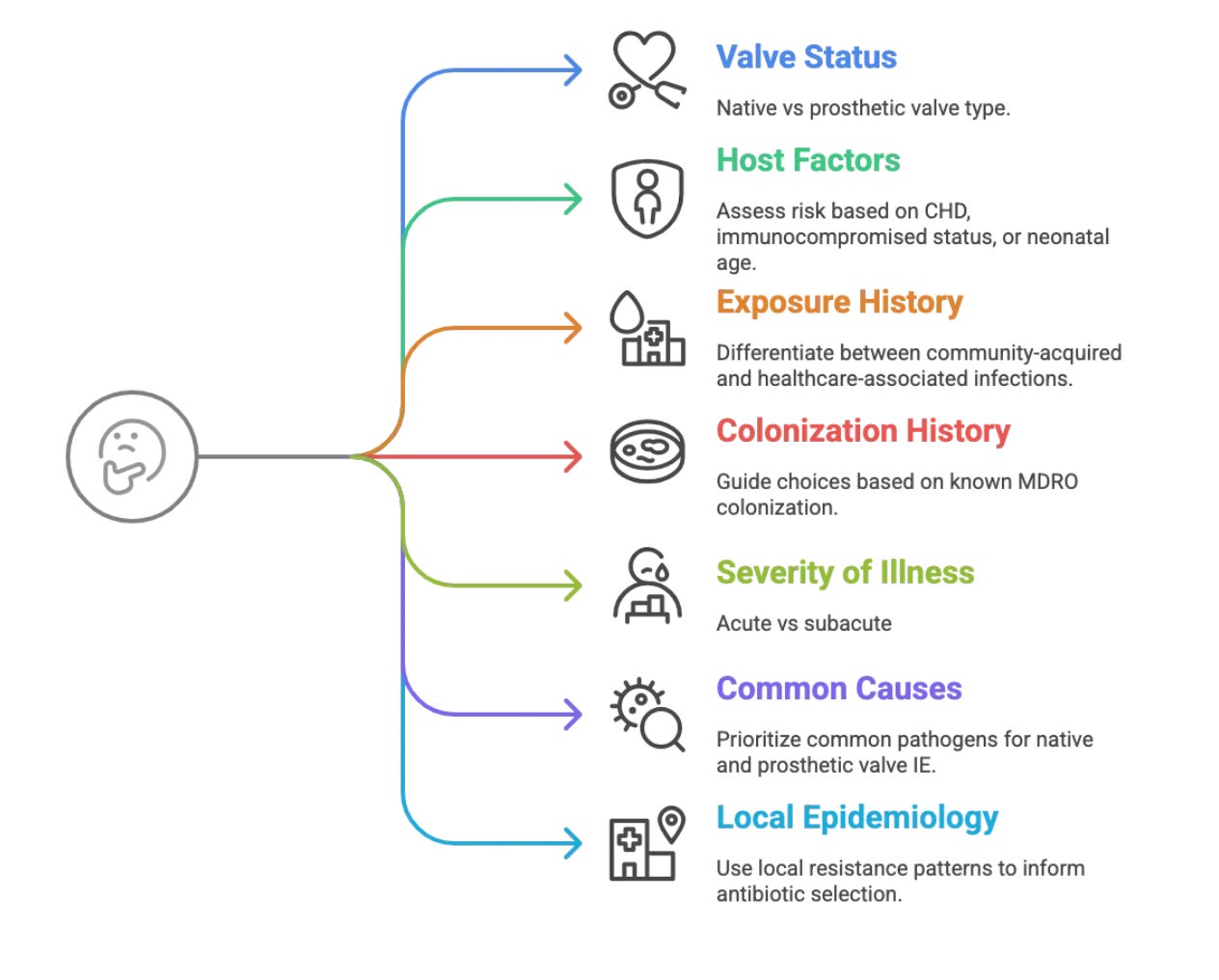

Treatment Game Plan: Hit Hard, Hit Fast, Then Tailor

Choosing the right antibiotics upfront—empirical therapy—is a critical first step after blood cultures are drawn. Here are some things to think about:

1. Valve Status

Native Valve IE: Think S. aureus, VGS, Enterococci.

Prosthetic Valve IE: Include CoNS, MRSA, fungi, GNB.

2. Host Factors

CHD: High risk for left-sided IE.

Immunocompromised: The host's ability to clear infection is impaired. Broader spectrum of pathogens (GNB, fungi, uncommon bacteria).

Neonates: Consider GBS, GNB, Candida.

3. Exposure History and Recent Infections

Community-acquired: VGS, MSSA.

Healthcare-associated: MRSA, CoNS, GNB, fungi.

4. Colonization History

Known colonization with MDROs (e.g., MRSA, VRE, ESBLs) should guide empiric choices. Up to 30% of BC will be positive with the same colonising organism.

5. Severity of Illness

Sepsis: Broad, rapid bactericidal coverage.

Subacute: May allow for more targeted empiric therapy, if clues are strong

6. Consider Most Common Causes Overall?

Always keep S. aureus, VGS, and Enterococci in mind for native valve IE.

For prosthetic material, CoNS joins S. aureus at the top of the list.

7. Local Epidemiology & Antibiograms

Crucial! What are the common resistance patterns in your hospital and community? Is MRSA prevalence high? Are ESBLs common in GNB? This local data is invaluable. Most labs would have an antibiogram- ask them for one. It looks something like this:

Broadly, the principles of treatment are:

Empirical - check your local guidelines

Urgent: Don't delay in a sick child.

Bactericidal agents: Essential for penetrating vegetations.

Broad-spectrum (guided by the framework above)

Synergy - The role of gentamicin synergy is being challenged, particularly in Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis, including both native valve and prosthetic valve endocarditis.

Definitive Therapy:

Rationalise based on culture and sensitivity results. This is key to reducing antibiotic exposure and toxicity. The challenge is when it is culture negative.

Prolonged IV course: Typically 4-6 weeks, sometimes longer for resistant organisms or complications.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM):

Essential for Vancomycin (target AUC/MIC or troughs 15-20 mcg/mL for severe infections; AUC-guided dosing is preferred if available)

Aminoglycosides (monitor peaks for efficacy and troughs for toxicity)

Supportive Care: Manage heart failure, ensure adequate nutrition (especially in growth-faltering children), and address complications.

Always consider if surgical intervention is possible.

I do apologise for this long post. Pediatric IE is a complex entity, but with a systematic approach to diagnosis and management, we can make a real difference for these vulnerable patients. Keep learning, stay curious, and never hesitate to reach out to your seniors and specialists!

(Disclaimer: This post is for educational purposes only and should not replace clinical judgment or established institutional protocols. Always consult with senior colleagues and specialists for individual patient care.)

Key References:

Vicent L, Luna R, Martínez-Sellés M. Pediatric Infective Endocarditis: A Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2022 Jun 5;11(11):3217. doi: 10.3390/jcm11113217. PMID: 35683606; PMCID: PMC9181776.

Baltimore RS, Gewitz M, Baddour LM, et al. Infective Endocarditis in Childhood: 2015 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(15):1487-1515.

Marín-Cruz I, Pedrero-Tomé R, Toral B, Flores M, Orellana-Miguel MÁ, Boni L, Belda-Hofheinz S, Prieto-Tato LM, Fernández-Cooke E, Epalza C, López-Medrano F, Rojo P, Blázquez-Gamero D. Infective endocarditis in pediatric patients: a decade of insights from a leading Spanish heart surgery reference center. Eur J Pediatr. 2024 Sep;183(9):3905-3913. doi: 10.1007/s00431-024-05606-3. Epub 2024 Jun 24. PMID: 38913227; PMCID: PMC11322191.

A review of infective endocarditis associated with congenital heart disease - ResearchGate, accessed May 30, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321154739_A_review_of_infective_endocarditis_associated_with_congenital_heart_disease

Recommendations for the practice of echocardiography in infective endocarditis - European Society of Cardiology, accessed May 30, 2025, https://www.escardio.org/static-file/Escardio/Subspecialty/EACVI/position-papers/recommendations-endocarditis.full.pdf

Ganesan V, Ponnusamy SS, Sundaramurthy R. Fungal endocarditis in paediatrics: a review of 192 cases (1971-2016). Cardiol Young. 2017 Oct;27(8):1481-1487. doi: 10.1017/S1047951117000506. PMID: 28857727.

Fungal Endocarditis - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed May 30, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532987/

Endocarditis in Children and Patients with Congenital Heart Disease ..., accessed May 30, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389307487_Endocarditis_in_Children_and_Patients_with_Congenital_Heart_Disease

Fowler VG Jr, Durack DT, Selton-Suty C, et al. The 2023 Duke-ISCVID Endocarditis Criteria: Updating the Modified Duke Criteria for the 21st Century. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(4):518-526. http://academic.oup.com/cid/article/77/4/518/7151107

Tissières P, Gervaix A, Beghetti M, Jaeggi ET. Value and limitations of the von Reyn, Duke, and modified Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis in children. Pediatrics. 2003 Dec;112(6 Pt 1):e467. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.e467. PMID: 14654647

DeSimone DC, Garrigos ZE, Marx GE, Tattevin P, Hasse B, McCormick DW, Hannan MM, Zuhlke LJ, Radke CS, Baddour LM; American Heart Association Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Blood Culture-Negative Endocarditis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association: Endorsed by the International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025 Apr 15;14(8):e040218. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.124.040218. Epub 2025 Mar 17. Erratum in: J Am Heart Assoc. 2025 May 6;14(9):e10928. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.124.035178. PMID: 40094211; PMCID: PMC12132861.

Park SY, Chang EJ, Ledeboer N, Messacar K, Lindner MS, Venkatasubrahmanyam S, Wilber JC, Vaughn ML, Bercovici S, Perkins BA, Nolte FS. Plasma Microbial Cell-Free DNA Sequencing from over 15,000 Patients Identified a Broad Spectrum of Pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2023 Aug 23;61(8):e0185522. doi: 10.1128/jcm.01855-22. Epub 2023 Jul 13. PMID: 37439686; PMCID: PMC10446866.