I’ve received many calls in the last week about this topic. Yes, there is an outbreak of measles here, but also in many parts of the world. One might think of measles as a relic of the past, a childhood illness largely conquered by vaccines. While vaccination has been incredibly successful, recent headlines from around the globe, including here in Australia, tell a different story: measles is back, and it's a serious threat. Overseas travel and immigration are rising again, while vaccination rates are dropping. Understanding this highly contagious virus is more important than ever.

What Exactly is Measles?

Measles is caused by a virus from the Paramyxoviridae family. Single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped RNA virus (more about what this means in another post). It only infects humans, meaning there's no animal reservoir we need to worry about. Critically, there's only one main type (serotype) of the virus, which is why the current vaccines work so well globally when used.

How Does it Spread? (Spoiler: Very Easily)

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known. It spreads mainly through the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or even just breathes. The virus particles can linger in the air for up to two hours after an infected person has left the room, meaning you can catch it without ever seeing the person who spread it. Direct contact with infectious droplets (like from a sneeze) is another route.

Its contagiousness is measured by the "basic reproduction number" or R0. For measles, the R0 is estimated to be between 12 and 18. This means one infected person, in a completely susceptible population, could infect, on average, 12 to 18 other people. To put that in perspective, the R0 for the original strain of COVID-19 was estimated around 2-3. Up to 90% of non-immune people exposed to measles will get sick.

What Does Measles Look Like? The Telltale Signs

Measles isn't just a simple rash. It typically follows a distinct pattern:

Incubation (7-21 days): After exposure, the virus multiplies silently. You feel fine, but the clock is ticking.

Prodrome (2-4 days): This is when you start feeling sick, often quite miserable. Symptoms include a high fever (often spiking over 40°C/104°F), a persistent cough, a runny nose (coryza), and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis) – often called the "three Cs".

Koplik Spots (Late Prodrome): About 1-2 days before the main rash, tiny white spots, like grains of salt on a red background, might appear inside the mouth, usually on the inner cheeks near the molars. These are considered a classic sign, though not everyone gets them or notices them.

The Rash (Appears 3-5 days after first symptoms): The characteristic measles rash emerges. It's typically a red, blotchy, maculopapular rash (meaning flat spots mixed with small raised bumps) that isn't usually itchy. It classically starts on the face/hairline and spreads downwards over the next few days, covering the body. The fever often spikes again when the rash appears. The rash lasts about 4-7 days and then fades in the same order it appeared, sometimes leaving a brownish discoloration or flaky skin.

Crucially, people are infectious for about 8-9 days total: starting 4 days before the rash appears and continuing until 4 days after it starts. This pre-rash infectiousness is a major reason it spreads so effectively before anyone realizes it's measles.

More Than Just a Rash: The Complications

Measles can be severe, and complications are common, affecting up to 30% of cases. Some are relatively mild, like ear infections (about 1 in 10 children) and diarrhoea (less than 1 in 10 people). But others are life-threatening:

Pneumonia: Lung infection occurs in about 1 in 20 children and is the most common cause of measles death in young kids. A recent case we saw presented as croup!

Encephalitis: Swelling of the brain happens in about 1 in 1,000 cases, potentially causing seizures, deafness, intellectual disability, or death.

Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE): A rare (perhaps 1 in 1,700 to 1 in 3,300 cases, higher if infected young) but always fatal degenerative brain disease that appears years after the initial infection. Although most people get away with, I do not wish anyone to experience the wrath of SSPE.

Death: Globally, measles caused an estimated 107,500 deaths in 2023, mostly among unvaccinated children under five. Even in developed countries, 1 to 3 out of 1,000 infected children may die. Recent US outbreaks saw the first deaths in nearly a decade.

Hospitalization: Many cases require hospital care – about 1 in 5 unvaccinated people in the US , with recent outbreaks showing rates as high as 40%.

Pregnancy Risks: For non-immune pregnant women, measles increases risks like premature birth or low birth weight.

Immune Amnesia: There is also this concept where measles infection can severely weaken the immune system for weeks, months, or even years afterwards, wiping out memory cells for other diseases and leaving people vulnerable to secondary infections.

Certain groups are at higher risk for severe measles: infants and young children (<5 years), adults (>20 years), pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems.

Airborne Precautions!

As soon as you think about the possibility of measles, ensure that the patient is isolated, and placed in a negative-pressure room. Recall that is spreads really easily.

How is Measles Diagnosed?

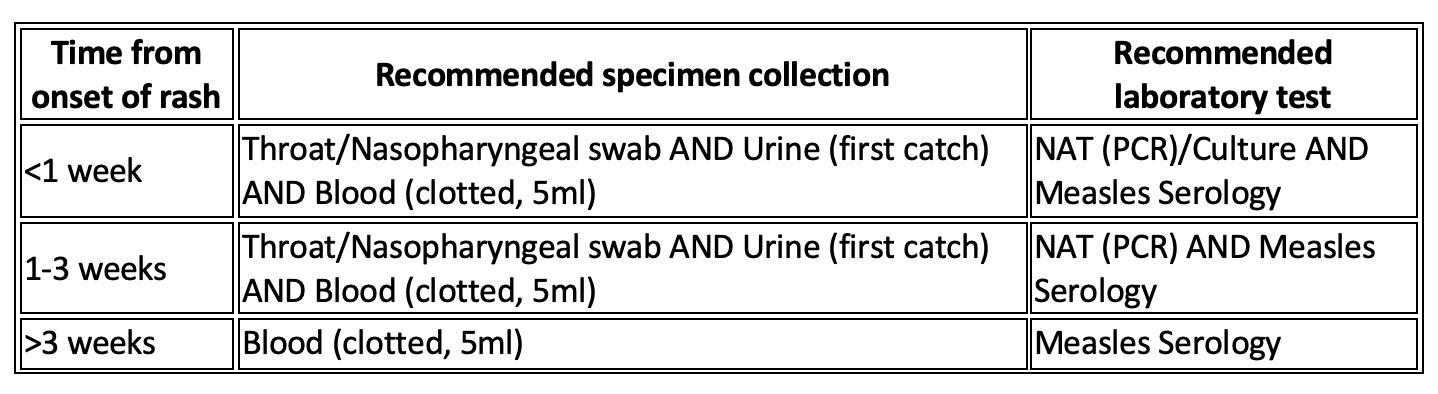

Laboratory testing is essential to confirm measles, especially for isolated cases or at the start of an outbreak. Recommended specimens include:

Molecular testing: Throat or nose swab, urine sample, and a blood for measles PCR (which looks for the virus's genetic material). Some laboratories have the capacity to differentiate wild-type measles, from vaccine-strain measles (see below).

Serology (which looks for measles-specific IgM antibodies in the blood, indicating a recent infection). Because IgM antibodies take a few days after the rash starts to become reliably detectable, both types of tests are often recommended. In the post vaccination era, IgG is usually reflective of past vaccination.

Measles Testing Guide Based on Time from Rash Onset

Importantly, healthcare providers should notify suspected cases immediately to public health authorities, even before getting test results back, to start control measures quickly.

Prevention: The Power of the MMR Vaccine

The good news? Measles is almost entirely preventable through vaccination. The MMR (Measles-Mumps-Rubella) and MMRV (which adds Varicella/Chickenpox) vaccines use a weakened live virus to trigger immunity without causing disease.

Schedule: In Australia, the routine schedule is MMR at 12 months and MMRV at 18 months. Anyone born during or since 1966 should ensure they have documentation of two doses (given at least 4 weeks apart, after 12 months of age) or proof of immunity via a blood test. If unsure, getting an extra dose is safe and recommended.

Efficacy: The vaccine is highly effective. One dose is about 93-95% effective. Two doses boost effectiveness to over 97-99%. This protection is considered lifelong for most people.

Safety: MMR/MMRV vaccines have an excellent safety record over decades. Mild side effects like fever or a faint rash can occur 5-12 days (typicially) post-vaccination. This is called vaccine-induced measles, but is not contagious. There's a small increased risk of febrile seizures (linked to the fever) after the first dose, especially with MMRV in toddlers. Serious side effects like severe allergic reactions are extremely rare. Importantly, numerous large-scale studies have definitively shown NO link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Why Outbreaks Still Happen: The Herd Immunity Gap

Because measles is so contagious, we need very high vaccination rates to protect the whole community – this is called herd immunity. For measles, the threshold is estimated at 92-95%. This means at least 95 out of 100 people need to be immune (mostly via two vaccine doses) to stop the virus from spreading easily and protect those who can't be vaccinated (like young infants or the immunocompromised).

Unfortunately, global vaccination coverage has slipped, partly due to pandemic disruptions. In 2023, global first-dose coverage was only 83%, and second-dose coverage was 74%. Even in countries like the US and Australia, which have eliminated endemic measles, coverage has dipped below the 95% target in some communities. Vaccine hesitancy is on the rise in many areas, including Australia, and yes Western Australia. These immunity gaps, combined with increased international travel, allow imported cases to spark outbreaks.

Responding to outbreaks is incredibly resource-intensive and costly for public health systems, involving extensive contact tracing and isolation measures. Studies show response costs often dwarf the direct medical costs, running into tens of thousands of dollars per case, and millions per outbreak. Prevention through vaccination is vastly more cost-effective.

Key Takeaway: Stay Vigilant, Stay Vaccinated

Measles is not a harmless childhood disease. It's a highly infectious virus with potentially severe consequences that is re-emerging globally due to gaps in vaccination. One might recover uneventfully in the immediate period, but complications can occur years down the track.

References

Measles CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/02/measles-cdna-national-guidelines-for-public-health-units.pdf

Measles - World Health Organization (WHO), accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

Measles | The Australian Immunisation Handbook, accessed April 16, 2025, https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/contents/vaccine-preventable-diseases/measles

Measles - United States of America, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON561

Vaccine hesitancy on the rise in WA. Medical Forum, accessed April 18, 2025, https://mforum.com.au/vaccine-hesitancy-on-the-rise-in-wa/