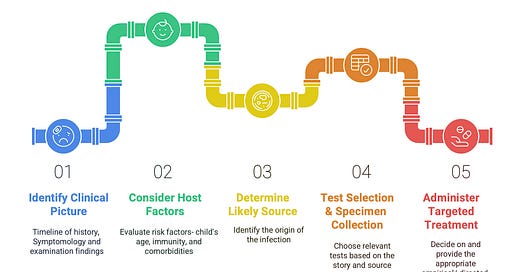

The 5-Step Infection Framework

A mental compass for approaching infections—practical, flexible, and made to stick.

Feeling overwhelmed when a child spikes a fever or comes down with something? You're not alone. Infections in kids can be confusing, worrying, and sometimes downright scary. Whether you're a medical student finding your feet and trying to make sense of symptoms, or a junior doctor on a busy ward, having a clear approach is crucial.

That's where this 5-Step Infection Framework comes in. Think of it as your mental compass – a practical, flexible guide to help you navigate the common (and sometimes uncommon) bugs kids pick up. It's designed to cut through the noise, focus your thinking, and help make sensible decisions. Yes, it can be used for any case where there is concern for infection.

Let's break it down.

Step 1: Gather the Story – What’s Actually Happening?

Every illness tells a story, and infections are no different. Before jumping to conclusions, ordering tests, or reaching for prescriptions, pause and listen. The child's story (often told by them or their caregiver) is usually your most powerful diagnostic tool. Ask yourself:

Timeline: Is this sudden (acute) or has it been brewing for days/weeks (chronic)? When did it really start?

Key Symptoms: What's actually bothering the child? Fever, cough, rash, pain (where?), vomiting, diarrhoea, lethargy? Get specific.

Sick or Well Child? This is critical. Beyond the specific symptoms, how does the child look and act? Are they still playful and drinking (generally well), or are they listless, refusing fluids, and looking truly unwell (sick)?

Red Flags: Are there any worrying signs? Difficulty breathing, stiff neck, non-blanching rash (doesn't fade with pressure), seizures, signs of dehydration (dry nappies/diapers, sunken eyes), extreme lethargy?

Exposures/Context: Any sick contacts? Recent travel? Daycare/school outbreaks? Vaccinated? Take the Infectious Diseases history (there’s a post for that!)

Why it matters: Details form patterns. A cough and runny nose starting yesterday differs from a fever and stiff neck developing over hours. Listening carefully often points you directly towards the likely problem, guiding your next steps far better than a scattergun approach to testing.

Step 2: Consider the Host – Who Is This Child?

An infection isn't just about the bug; it's about the unique child fighting it. The same virus or bacteria can cause mild sniffles in one child and a serious illness in another. Always consider the individual:

Age: This is huge! A fever in a 2-week-old neonate is treated very differently than a fever in a robust 4-year-old due to their immature immune systems and different likely pathogens.

Immune Status: Is the child's immune system working normally? Consider factors like:

Prematurity

Underlying conditions (e.g., congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis)

Medications (e.g., chemotherapy, long-term steroids)

Known immunodeficiencies

Medical Devices: Do they have central lines, VP shunts, tracheostomies, or urinary catheters? These can be potential entry points or sources for infection.

Underlying Conditions: Does the child have other health issues (like asthma, diabetes, kidney problems, or a genetic disorder) that might affect how they handle an infection or influence treatment choices?

Vaccination History: Are they up-to-date? This affects the likelihood of certain vaccine-preventable diseases (like measles or pneumococcal infection). Check the records, and beware of homeopathic vaccinations- these are not approved vaccines.

Why it matters: You aren't just treating an abstract "infection"; you're treating this specific child. Understanding their unique vulnerabilities and strengths is key to anticipating risks and tailoring management.

Step 3: Pinpoint the Likely Source – Where Is It Coming From?

"Sepsis" or "infection" describes a state, not a location. To treat effectively, you need to figure out where the infection is likely hiding. Based on the story (Step 1) and the host factors (Step 2), where does the evidence point?

Respiratory Tract: Lungs (pneumonia), airways (bronchiolitis, croup), throat (tonsillitis), sinuses (sinusitis), ears (otitis media)?

Urinary Tract: Kidneys (pyelonephritis) or bladder (cystitis)?

Gastrointestinal Tract: Stomach/intestines (gastroenteritis)?

Central Nervous System (CNS): Brain/spinal cord coverings (meningitis) or brain tissue itself (encephalitis)?

Skin and Soft Tissue: Cellulitis (skin infection), abscess?

Bones or Joints: Osteomyelitis (bone infection), septic arthritis (joint infection)?

Bloodstream: Bacteraemia (bacteria in the blood – often secondary to another source)?

Device-Related: Infection linked to a line, shunt, etc.?

Why it matters: Knowing the likely source is fundamental. It determines which tests are most useful (e.g., urine test for suspected UTI, chest x-ray for suspected pneumonia) and which treatments (especially antibiotics) will reach the site of infection effectively. "Treating sepsis" without identifying the source is like flying blind.

Step 4: Choose the Right Tests (At the Right Time)

Tests should confirm or clarify what you suspect based on the first three steps, not replace clinical judgment.

Tailor Your Tests: Order tests directly addressing the likely source identified in Step 3. Don't order everything "just in case."

Quality Over Quantity: A poorly collected sample can be misleading or useless. How you collect your specimens, and how quickly it gets to the lab matters! For example:

A urine sample contaminated with skin bacteria isn't helpful. Aim for a "clean catch" or catheter sample if needed.

Blood cultures before starting antibiotics give the best chance of identifying bacteria.

A wound swab transported at high temperatures and reaching the lab four days later may exhibit overgrowth of skin commensals or may fail to grow.

Timing Matters:

Collect cultures (blood, urine, CSF) before giving antibiotics whenever possible (without causing harmful delays in sick children).

Sometimes observing the child's response over time is more informative than immediate testing, especially for common viral illnesses.

Why it matters: Unnecessary tests can lead to confusion, false positives, incidental findings, and unnecessary costs or procedures. Thoughtful, targeted testing provides high-value information. Remember: a poor-quality sample is often worse than no sample at all.

Step 5: Target the Treatment – What’s the Plan?

Now, synthesis time. Based on the story, the host, the likely source, and any test results, what does this child need?

The Biggest Question First: Are antibiotics actually needed? Many common childhood infections (colds, coughs, most sore throats, stomach bugs) are caused by viruses. Antibiotics do not work against viruses and can cause side effects (like diarrhoea, rash, thrush) and contribute to antibiotic resistance. Supportive care (fluids, rest, pain/fever relief) is often the main treatment.

If YES to Antibiotics:

What bug are you targeting? Based on the likely source and local resistance patterns.

Which antibiotic? Choose one that covers the likely bacteria and gets to the source effectively (e.g., some antibiotics penetrate the brain/CSF better than others). Aim for the narrowest spectrum possible that will do the job.

Route? Can the child tolerate oral medication, or do they need intravenous (IV) antibiotics?

Duration? How long is treatment needed? Shorter is often better if clinically appropriate.

Don't Forget Supportive Care: Regardless of antibiotics, managing fever/pain, ensuring hydration, and monitoring the child are crucial.

Review and Adjust: Reassess the child's progress. Are they improving? Are culture results back? Do you need to change the antibiotic or stop it altogether?

Why it matters: The goal is effective treatment with minimal harm.

Key takeaway: The best antibiotic is often the one you didn’t have to use. But if you must—choose wisely, target narrowly, and use it for the right duration.

In Action: A Quick Case

Let's apply the framework:

Scenario: A generally healthy 3-year-old girl presents with a 2-day history of fever, crying when she pees (dysuria), and some mild lower tummy pain. She's a bit grumpy but still drinking okay and has no respiratory symptoms or rash.

Applying the Framework:

Story: Acute onset, localised urinary symptoms (dysuria, pain), looks relatively well, no major red flags noted.

Host: Healthy, vaccinated 3-year-old – low risk generally.

Source: Story strongly points to the Urinary Tract (UTI).

Tests: A clean-catch urine sample for analysis and culture is the priority. Blood tests are unlikely needed given she looks well.

Treatment: Likely needs antibiotics for a probable bacterial UTI. Start an appropriate oral antibiotic (covering common UTI bugs like E. coli) pending the urine culture results. Ensure good fluid intake. Review when culture results are available.

Outcome: Framework applied. A sensible, safe, and targeted approach without unnecessary tests or interventions.

Hope this helps! Share your insights or questions in the comments below!

If you found this useful, consider subscribing to "Bugged Out" for more practical insights into an Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiologist’s mind.